https://vita.com.bo/ambien-mexico-online The dead can’t tell their stories. Even when their accounts are documented, they are often given less credence than the accounts of survivors who still exist to share theirs. Simply put, survivorship bias is a logical fallacy in which we concentrate on the accounts of those who have made it past some criteria and overlook the accounts of those who did not. The error is compounded as conclusions are drawn that suggest that success is due to some characteristic shared by the successful instead of extraneous variables or random chance.

Zolpidem Sleeping Tablets Buy I most often see this bias play out in three ways:

https://forumlenteng.org/buy-ambien-online-overnight- “The secret to a long life” stories

- “I did XYZ as a child, and I turned out fine” stories

- “Rags to riches” stories

https://www.ag23.net/zolpidem-cheapest Even though some of these stories may be shared with a humorous intent, there are plenty of examples where people believe that they are drawing accurate conclusions about success based on a selective review of attempts in pursuit of that success.

https://habitaccion.com/buying-zolpidem-ukThe secret to a long life

https://www.magiciansgallery.com/2024/06/buy-zolpidem-online Whenever someone reaches the 100 year mark, people clamor to know what their secret to a long life has been. No surprise, the answer will always be whatever it is that person has done. When George Burns was approaching centenarian status, people noted some of his more counterintuitive characteristics–his daily drinking and cigar smoking–as the key to a long life. These reflections may have been shared in jest, but repetition of fallacious logic reinforces the idea that we can draw conclusions based on our observations, which obviously ignores the accounts that we lack access to. Burns’ longevity is much more likely attributable to his balanced, modest diet and daily exercise routine, though we can still cannot make a causal inference.

https://starbrighttraininginstitute.com/online-zolpidem-tartratehttps://forumlenteng.org/order-ambien-uk In 2015, a 104 year old Fort Worth resident attributed her long life to her daily intake of Dr. Pepper. It’s a light-hearted, feel-good human interest story, but of course, there’s no empirical evidence that drinking any particular beverage extends life or refraining from drinking it shortens it, aside from perhaps water. Besides, her love of Dr. Pepper only began at age 60. So perhaps the lesson is to take up a soft drink addiction at retirement age to live a long, healthy life.

I did XYZ as a child and turned out fine

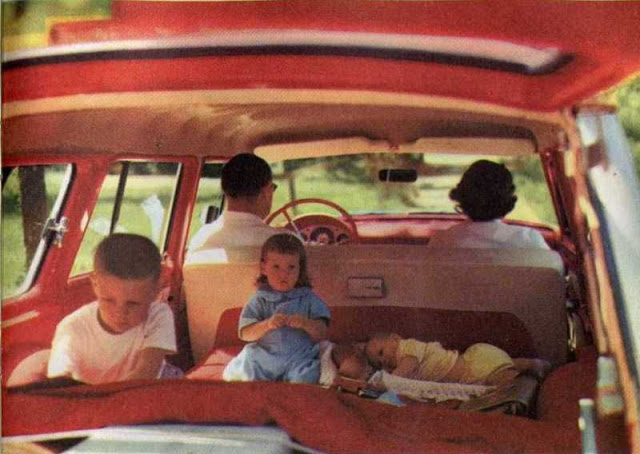

https://habitaccion.com/order-ambien-online-overnight These stories can often be told in the same humorous light as the above instances, though we begin to cross into dangerous territory here as people use this version of the fallacy to argue against some kind of reform simply because they survived without it. On the humorous side, we have pictures from yesteryear of children playing, unrestrained, in the back of a moving station wagon. “Like and share if you ever played in the back of a moving car and lived to tell the tale!” the picture will say. And people will like and share. Guess who can’t like or share? Those who flew through the windshield or broke their neck colliding with the seatback during a fender bender. It’s humorous, even if darkly so, to look back at the dangers of our youth and ponder our survival despite them. It’s less humorous to suggest that wearing helmets or seatbelts represents a weakening of our society when our forebears endured so much more.

https://creightondev.com/2024/06/24/buy-zolpidem-online-canada

https://creightondev.com/2024/06/24/buy-ambien-american-express This picture is from a very clickbait-y article called, “18 Photos That Prove the Station Wagon Was Actually the Best Family Car Ever.” Besides trying to assert opinion as fact, the photos seem only to confirm that the station wagon was a car used by families, not that it was good for them or their survival. The data are clear: seat belts save lives. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in 2017, just under 15,000 lives were saved by wearing seatbelts. The CDC reported for 2016 that over half of crash fatalities among those aged 13-44 were not buckled up. Just because you survived riding around unbuckled doesn’t mean anything. You’re not evaluating the accounts of those who were maimed in accidents or who are no longer alive to give caution against such a claim. It’s not just seatbelts. This form of survivorship bias, often coupled with confirmation bias, is used to decry law changes or innovations in many health and safety related claims.

https://makeitagarden.com/best-price-ambien-onlineRags to riches

https://exitoffroad.com/buy-ambien-online-visa This is my least favorite iteration of this fallacy. Unlike the above archetypes, there’s little room for humor in this one. The mood of this argument rests on the assumption that so-and-so achieved such-and-such, and you have no excuse for not being able to achieve the same. On its surface, it should be easy to see how poor that logic is, but people appeal to this bias frequently when shaming others for not having reached whatever milestone is being discussed. Like above, only the successful cases are considered with no light shed on the failures, the proportion of successes to failures, or the variable conditions that may otherwise have contributed to success.

https://www.magiciansgallery.com/2024/06/buy-ambien-cheapestBuy Ambien Overnight Cod This fallacy is the basis of every “bootstraps” argument of self improvement. You too could have a nice job, earn more, continue your education, climb out of poverty, own a home, start a business, etc. if only you pick yourself up by your bootstraps and put in the hard work. This is deeply ingrained in American culture especially as people are programmed from an early age to believe that success and prosperity result from effort which is not the case. I could easily fill an entire post with the many false assumptions of equality that persist in society, but that’s a rabbit hole for another day. Sufficed to say that the earning power of one’s parents, the educational level of one’s parents, and the neighborhood in which one grows up in are all stronger predictors of success than some unquantifiable metric based on effort. People who grew up poor who are not poor as adults love to share their anecdotal evidence as a blueprint for escaping poverty. They did it. Why can’t you? They view their relative success and those of others they may know as a reassurance of this capacity for upward mobility. Whose stories are not heard? You guessed it: all of the people who toil away, work hard, exert effort, tug on bootstraps but still cannot escape poverty. In the same vein is ignoring the assistance people had access to that helped them move upward. Jeff Bezos did not start Amazon in a garage. He started Amazon in a garage after working a decade on Wall Street and with a loan from his parents of almost $250,000. People leave that out. How many people reading this can go to their parents for a loan of $250,000? And even if 100% of people reading this could do that, it still wouldn’t be evidence that others can do the same. Even still, starting with a fat stash of seed capital isn’t a guarantee of success. There are many sources outlining the mortality rates of startup businesses.

Zolpidem Sale OnlineIn closing

https://makeitagarden.com/order-zolpidem-tartrate-online You can’t look to the survivors for a way forward. That’s surface-level thinking, and it’s not a productive way to process our incredibly-complex and interconnected world. Improve your thinking by always asking questions and seeking a deeper understanding. “What other factors might be at play here?” “What other accounts am I not seeing or hearing?” As with many things, if it sounds too good to be true, it just might be.

Leave a Reply